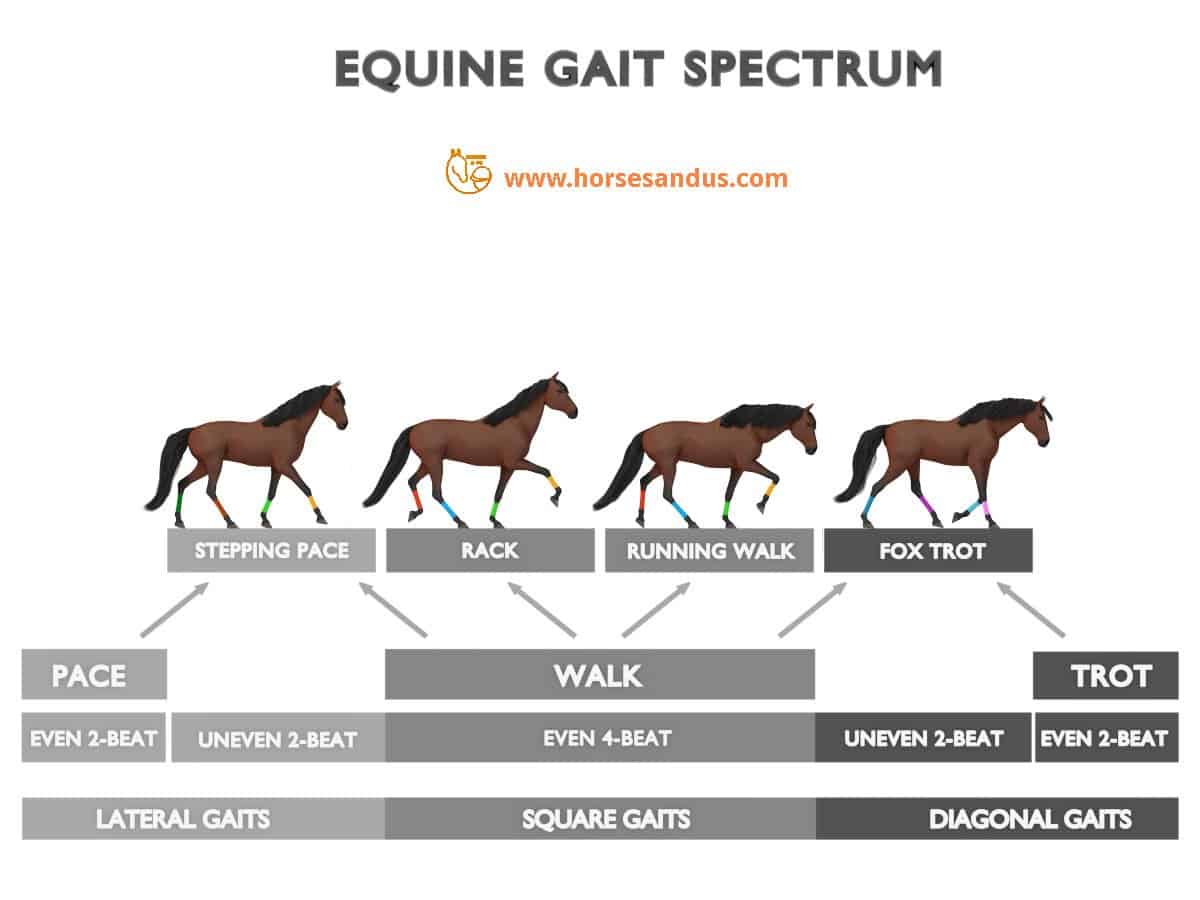

A gait is a distinct form of movement where the limbs move in a specific rhythmic pattern at a particular speed. As the horse changes speed, he transitions to another gait.

Horses can perform a large number of gaits. Some gaits are unique to certain breeds, some gaits are acquired through training, and some gaits are natural to almost all horses and are considered the 4 basic gaits.

The 4 basic horse gaits, in increasing order of speed, are the walk, the trot, the canter, and the gallop.

Horse Gait Cycle Terminology

Next, we will explain some basic gait terminology.

Symmetrical vs. Asymmetrical Gaits

Depending on the pattern of the limb movement, gaits can be classified as symmetrical or asymmetrical.

Symmetrical gaits, such as walk and trot, have the limb pattern on one side repeated on the other side (half a stride later).

In Asymmetrical gaits such as canter and gallop, the limb pattern on one side does not repeat on the other side.

Stride

A Stride is a gait cycle, in which all 4 limbs complete their movement.

A particular gait is composed of a series of similar strides. So a stride can be considered a “unit” of a gait.

Stance Phase and Swing Phase

During a stride each leg has a stance phase and a swing phase:

- The stance phase is when the hoof is in contact with the ground, which includes:

- Impact (footfall) – when the hoof hits the ground.

- Breakover (lift-off) – when the hoof leaves the ground.

- The Swing phase is when the hoof has no contact with the ground

The terminology is described using a reference leg which is highlighted in the following example of the horse walk cycle.

Beat

Each individual footfall within a stride corresponds to a beat.

For example, there are 4 individual footfalls in the walk, so it is called a 4 beat gait. In the trot, there are 2 individual footfalls, so it is called a 2 beat gait.

Supporting Limbs

At any moment during the stride the horse may be supported by a different number of limbs:

- Single limb (unipedal support)

- Two limbs (bipedal support)

- Three limbs (tripedal support)

Each gait has a particular sequence of supports.

Generally, an increase in speed within each gait and across gaits results in fewer limbs supporting the body.

Typical support sequences for each stride are as follows:

- Walk – 3:2:3:2:3:2:3:2

- Trot – 2:0:2:0

- Canter – 1:3:2:3:1:0

- Gallop – 1:2:1:2:1:2:1:0

Horse Walk

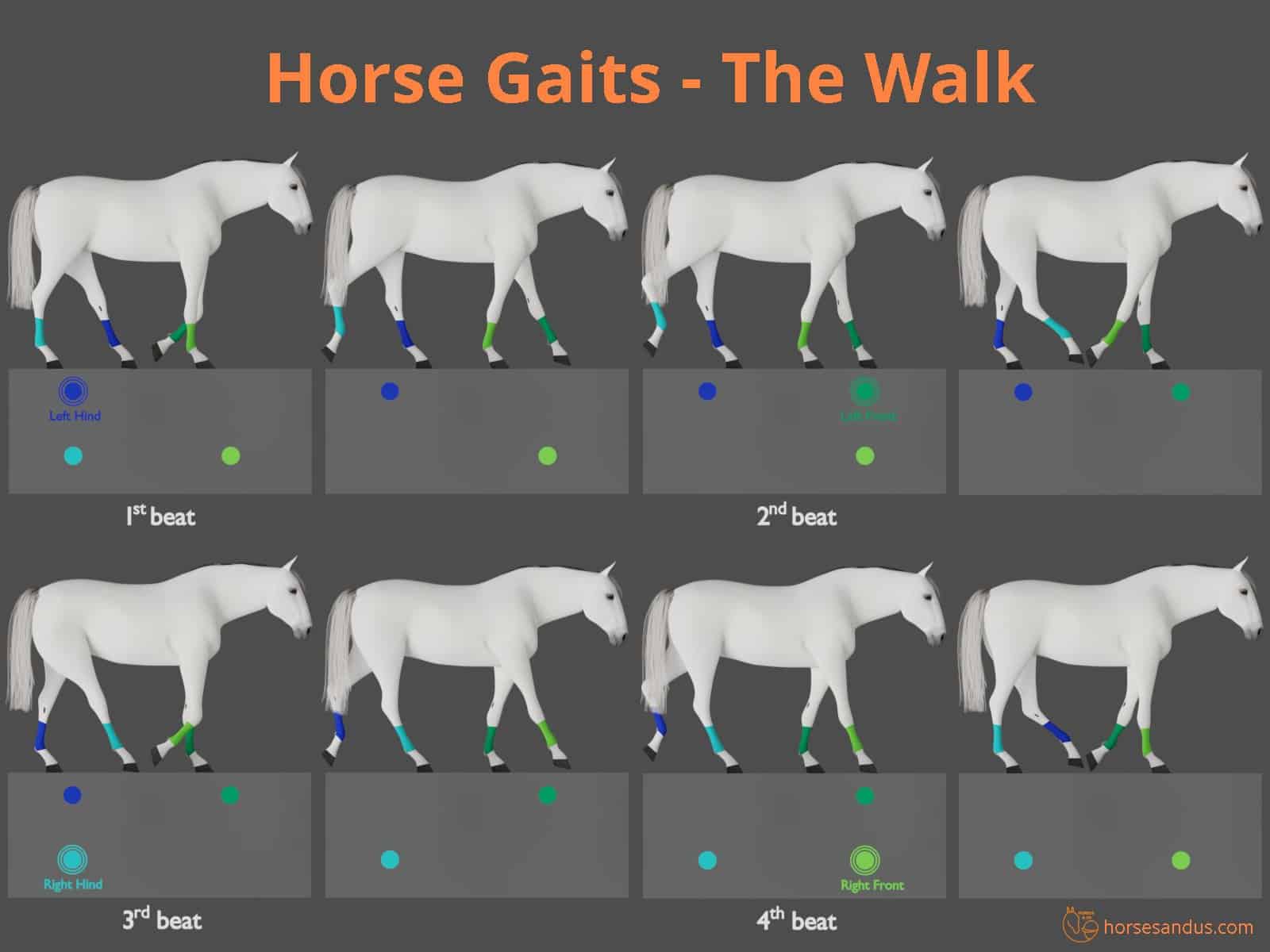

The walk is a slow, symmetrical, four-beat gait. It is characterized by four distinct beats, where each hoof lands on the ground at a separate interval, independent of the other hooves.

The footfall sequence is:

Left Hind – Left Front – Right Hind – Right Front.

Ideally, the walk should have a consistent four-beat rhythm, where the four footfalls of the walk are spaced with equal intervals of time. The stride length should also be similar, and with over-tracking, i.e., the hind hoof should surpass the print made by the front hoof.

The walk does not have any aerial phase, i.e., when all hooves are in the air. At any moment, there are always 2 or 3 hooves on the ground.

In the walk, the horse moves its head up and down to help him maintain his balance.

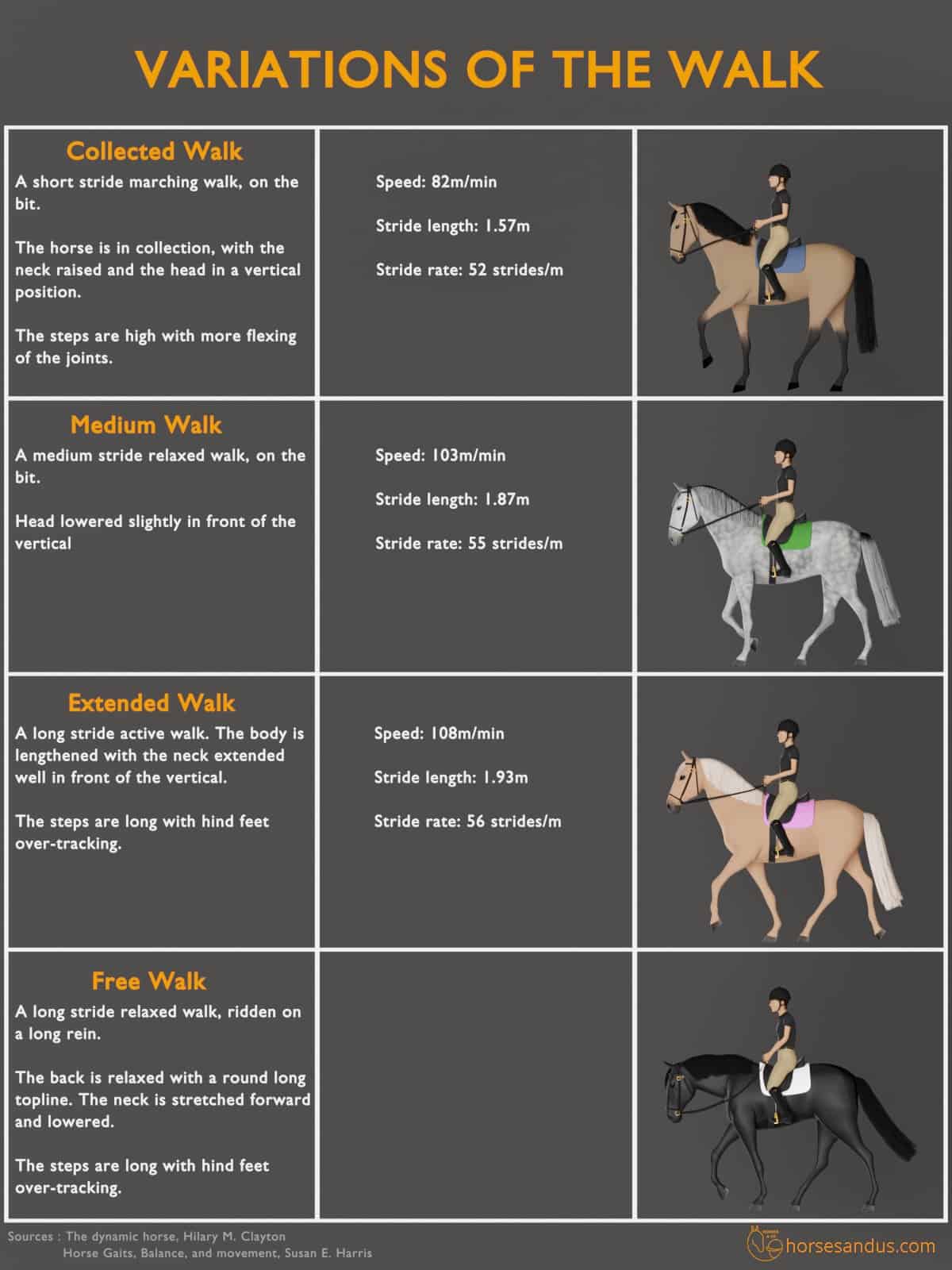

Variations Of The Horse’s Walk

There are variations in the speed, stride length, and height of the walk.

Horses can have their walk trained in different ways for certain disciplines. For example, in dressage competitions, there are four variations of the walk: collected walk, medium walk, extended walk, and free walk.

Different breeds may also have a different characteristic walk. For example, the quarter horse has a very relaxed motion, while the American Saddlebred has a high flexing of the knee.

Faults In The Horse’s Walk

Young horses usually have a “good” walk, using their neck and head appropriately. However, when they start to be ridden, their walk will often become irregular because they cannot move freely when they are on the bit.

The most common pattern we can observe in a faulty walk is when the four-beat gait comes closer to two beats. This happens when the hindlimb and forelimb move almost simultaneously, without a clear perception of distinct footfalls. This is usually caused when the horse is tense.

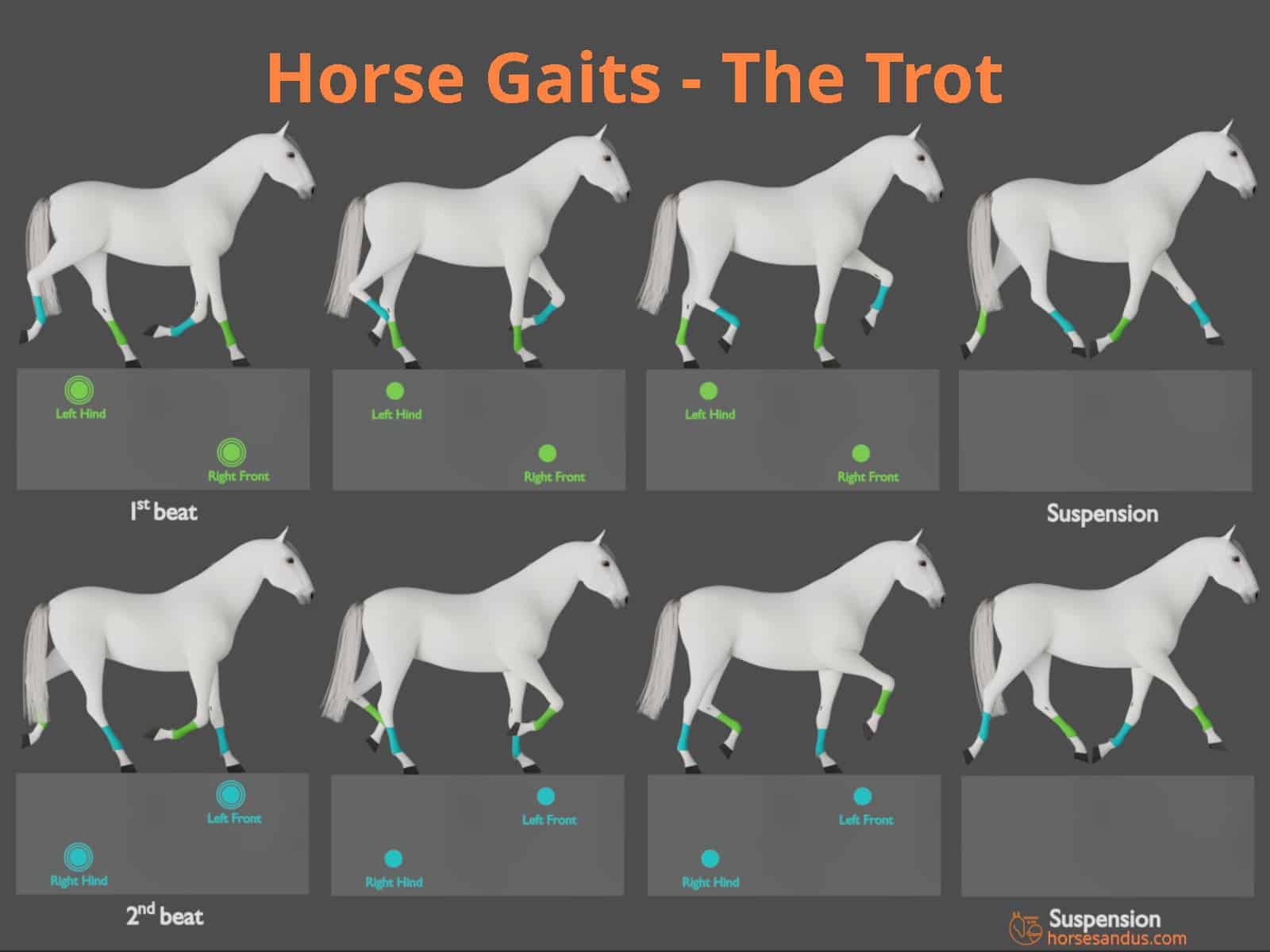

Horse Trot

The trot is a rapid, symmetrical, two-beat diagonal gait. It is characterized by two distinct beats with a period of suspension between the beats. The first beat comes when a diagonal pair of limbs hit the ground together, this is followed by a period of suspension, after which the other diagonal pair hit the ground for the second beat.

The footfall sequence is:

Left Hind + Right Front – Suspension – Right Hind + Left Front – Suspension

This sequence repeats rhythmically. The beats, intercalated with moments of suspension, give the trot its characteristic spring and bounce motion.

Rising Trot vs. Sitting Trot

The trot can be ridden in two ways: Sitting trot or Rising (posting) trot.

- In the sitting trot, the rider is always in contact with the saddle. This requires the rider to be more experienced.

- In the rising trot, the rider is off the saddle in one of the beats and on the saddle in the other beat. This allows the rider to more easily maintain balance and is more appropriate for novice riders.

The trot is the best gait to detect lameness

The trot is a balanced, symmetrical, straightforward movement, where the diagonal limbs move in unison, with the hind lower leg parallel to the front upper leg. Because it is a symmetrical gait, the trot’s correctness is evaluated on its symmetry features.

The trot’s regular and balanced movement makes it easy to detect any abnormalities. If the horse is lame, it may not show in the walk or canter, but it can be easily seen in the trot, with head bobbing being a classical sign of lameness.

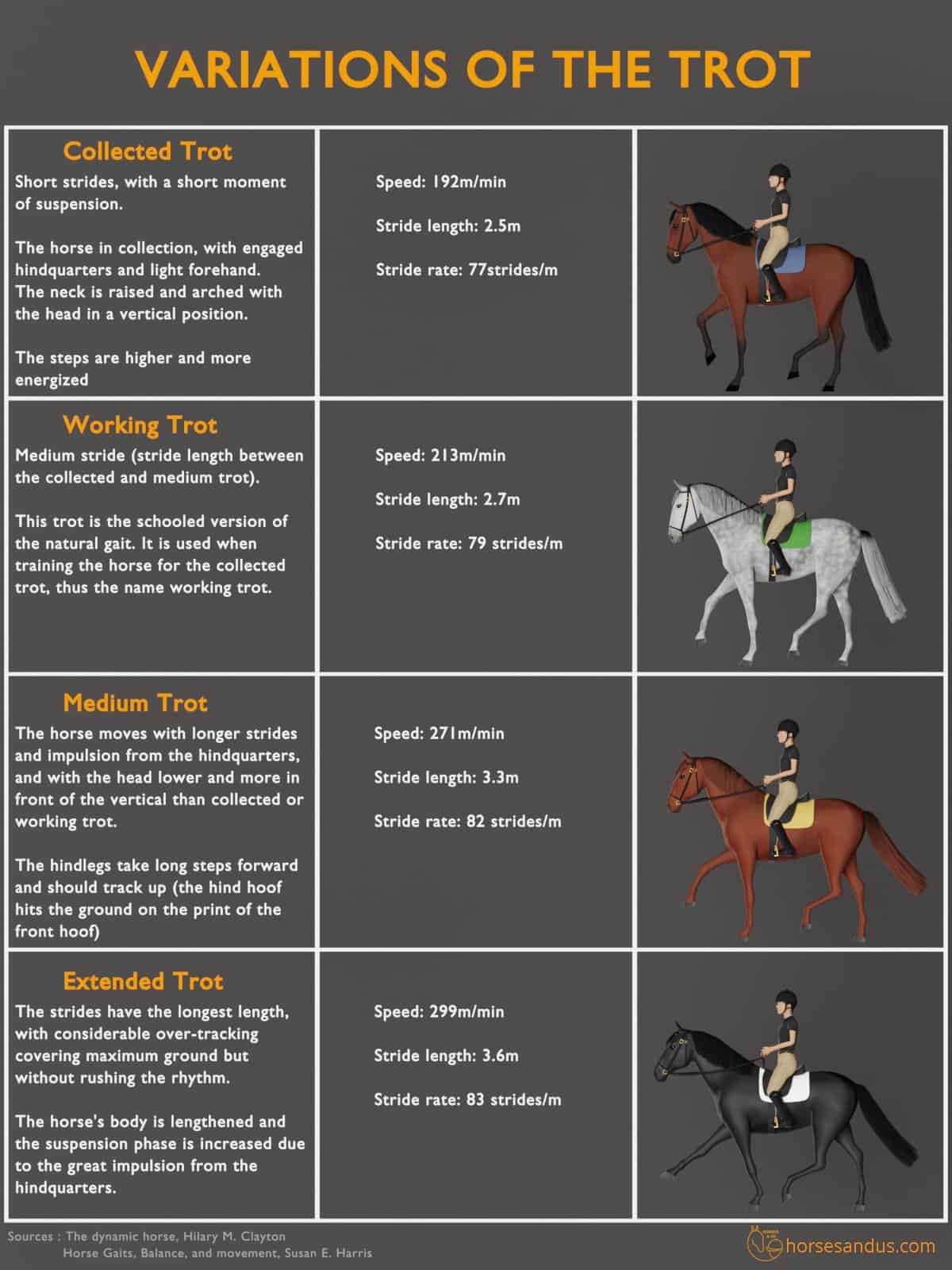

Variations Of The Horse’s Trot

The trot can vary in its speed and stride length. The variations in the speed of the trot are achieved by changing the stride length. Ideally, the rhythm should remain the same, so the horse must lift his legs higher as the stride increases.

Dressage horses are trained to perform four trot variations: collected trot, working trot, medium trot, and extended trot.

Faults In The Horse’s Trot

Not all horses have a perfectly balanced and regular trot. When the horse is being ridden, we can often observe a tense horse with a stiff and hollow back and head carried high above the bit or behind the bit.

The most common faults are:

- Uneven rhythm, where the horse takes quick, slow, or irregular steps.

- Irregular trot, where the diagonal pair do not move in unison.

- Forging, which occurs when the hindfoot hits the front hoof on the same side. This happens when the front hoof of the diagonal pair hits the ground before the hind hoof and is often caused by too much weight on the forehand.

- “Out behind,” where the hind limbs move farther behind than they reach forward. This can be due to the horse’s conformation, loss of balance, or a tight and hollow back.

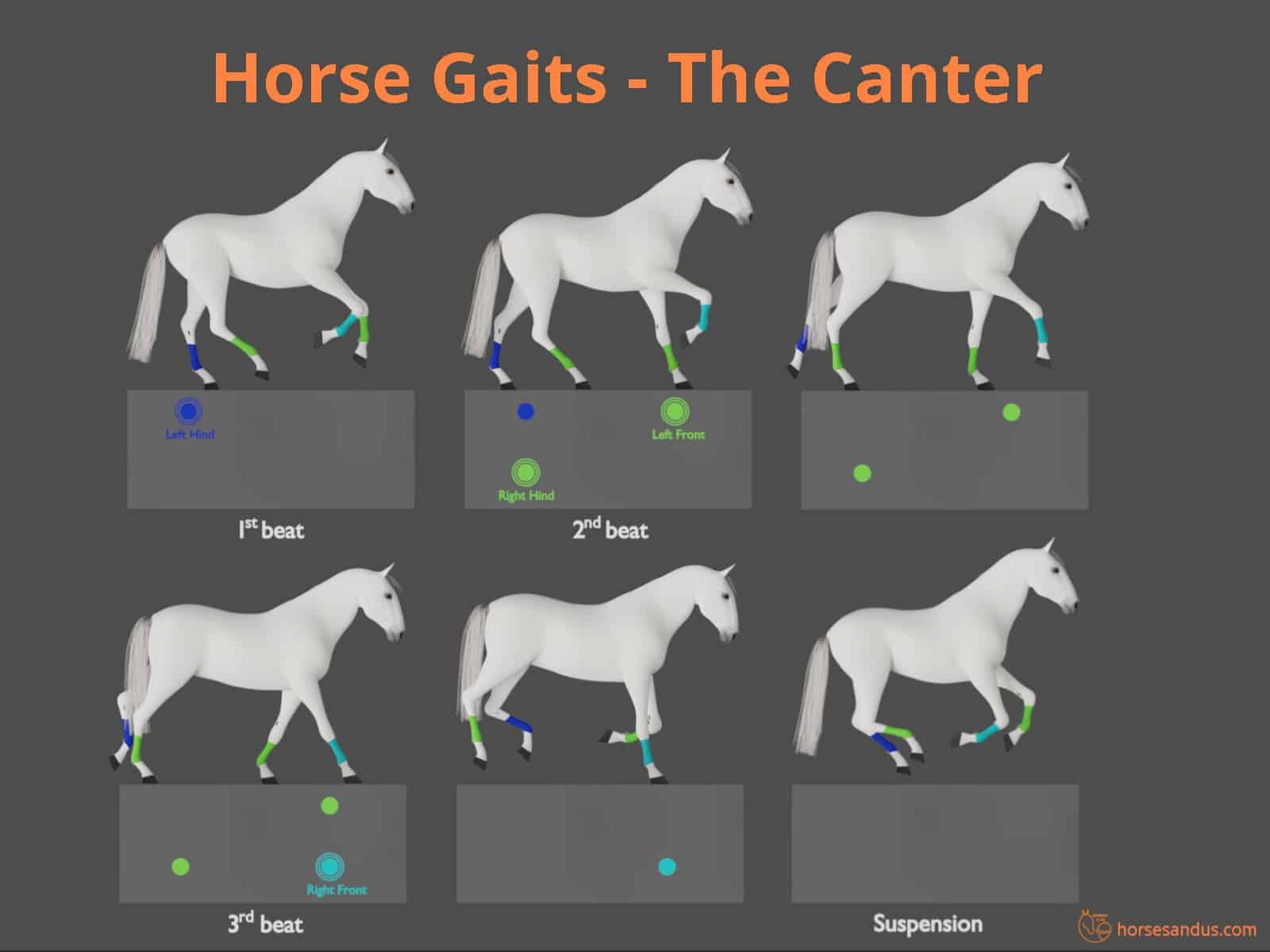

Horse Canter

The canter is a fast, asymmetrical, three-beat gait. It’s characterized by a rocking motion with a series of bounces and a moment of suspension. In the first beat, one hind hoof hits the ground; in the second beat, the opposite hind hoof and diagonal front hoof hit the ground; finally, in the third beat, the remaining front hoof hits the ground.

The footfall sequence is:

Right Lead Canter

Left Hind – Right Hind + Left Front – Right Front – Suspension

Left Lead Canter

Right Hind – Left Hind + Right Front – Left Front – Suspension

This sequence is repeated in a regular 1,2,3, pause, 123, pause….

The 3 beats (1,2,3) form a rocking motion followed by a bounce in the air.

The Leading Limb in the Canter

In the canter, the horse can be either in the right lead or left lead, depending on which limb is leading. The leading limb is the last front limb to leave the ground before the moment of suspension.

The horse should lead with the inside leg, which helps support the horse and makes it easier for him to balance. So when he is turning left, the left leg should lead, and when turning right, it should be the right leg leading. Horses naturally change leads before they make a sharp turn in a new direction.

The leading limb supports the heaviest burden. Therefore when cantering in a straight line, the horse may sometimes change leads to avoid tiring the leading limb. Also, when riding a horse in a circle, the rider should occasionally change direction so the burden can be shared between the leading limbs.

The Flying Change

The switch between leads during the moment of suspension is called a “flying change.” This movement is trained at the beginning of upper-level dressage, where the change must be made with both front and hind legs during the same moment of suspension.

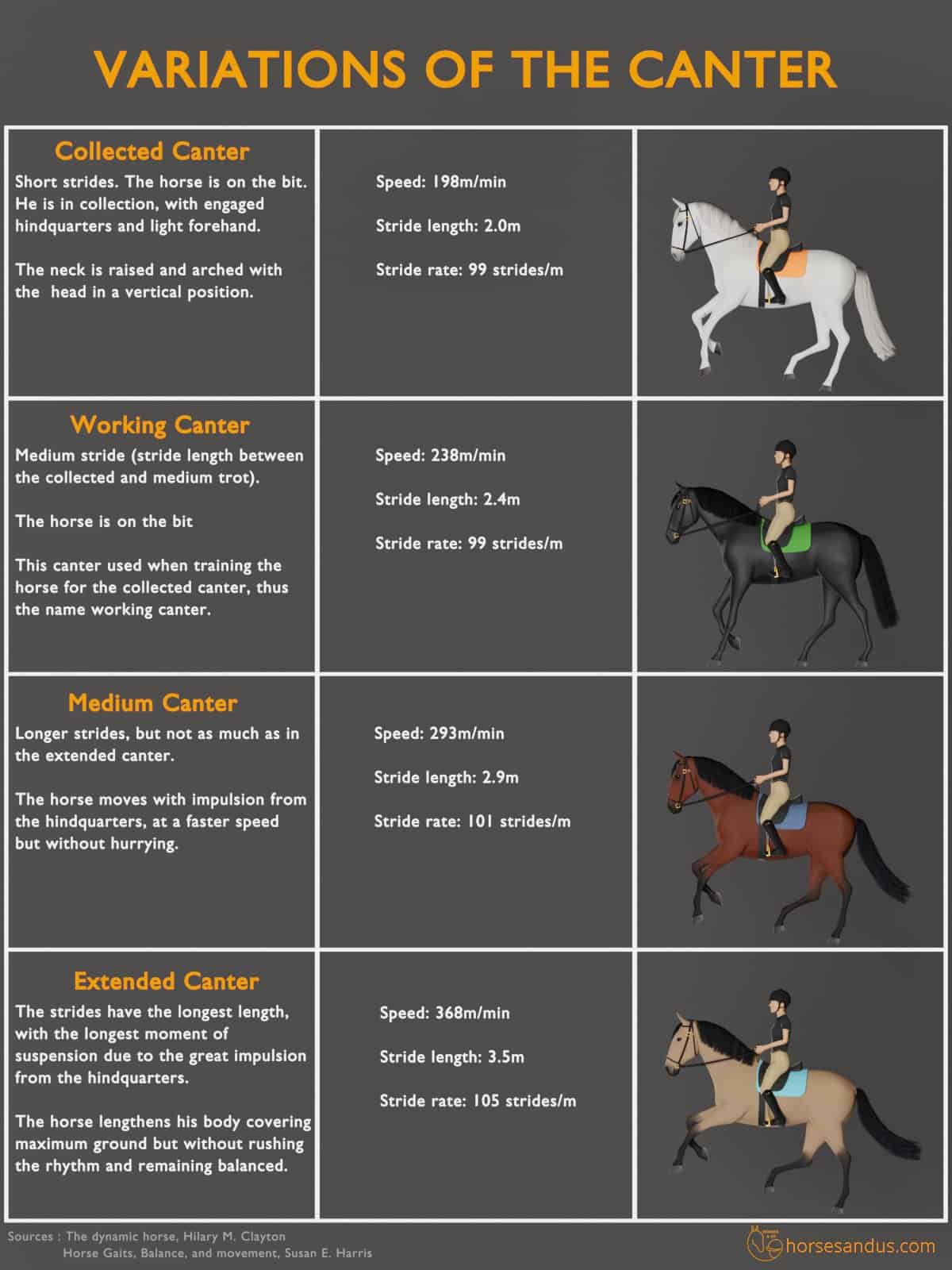

Variations Of The Horse’s Canter

There are variations in the canter. “These vary in speed, with the differences being achieved by changing stride length while maintaining an almost constant stride rate.”(Clayton 1994)

Dressage horses are trained to perform four canter variations: collected canter, working canter, medium canter, and extended canter.

Faults In The Horse’s Canter

When the horse is being ridden, especially in a circle, we can often observe faults in the canter.

These problems often are caused by a natural asymmetry and the lack of engagement from the hind legs, which leads to an imbalance in the canter.

Common problems are:

- Wrong lead

- Irregular four-beat canter (which resembles cantering with front limbs and trotting with back limbs)

- Bucking

- Speeding downhill

- “Pacey” canter (when the legs on the same side move almost together, resembling a pace)

- Disunited canter or cross-canter (when the horse canters on one lead in the front legs and the other lead in the hind legs and the second beat is done with the legs on the same side instead of diagonals). This great video below shows how to identify a disunited canter clearly.

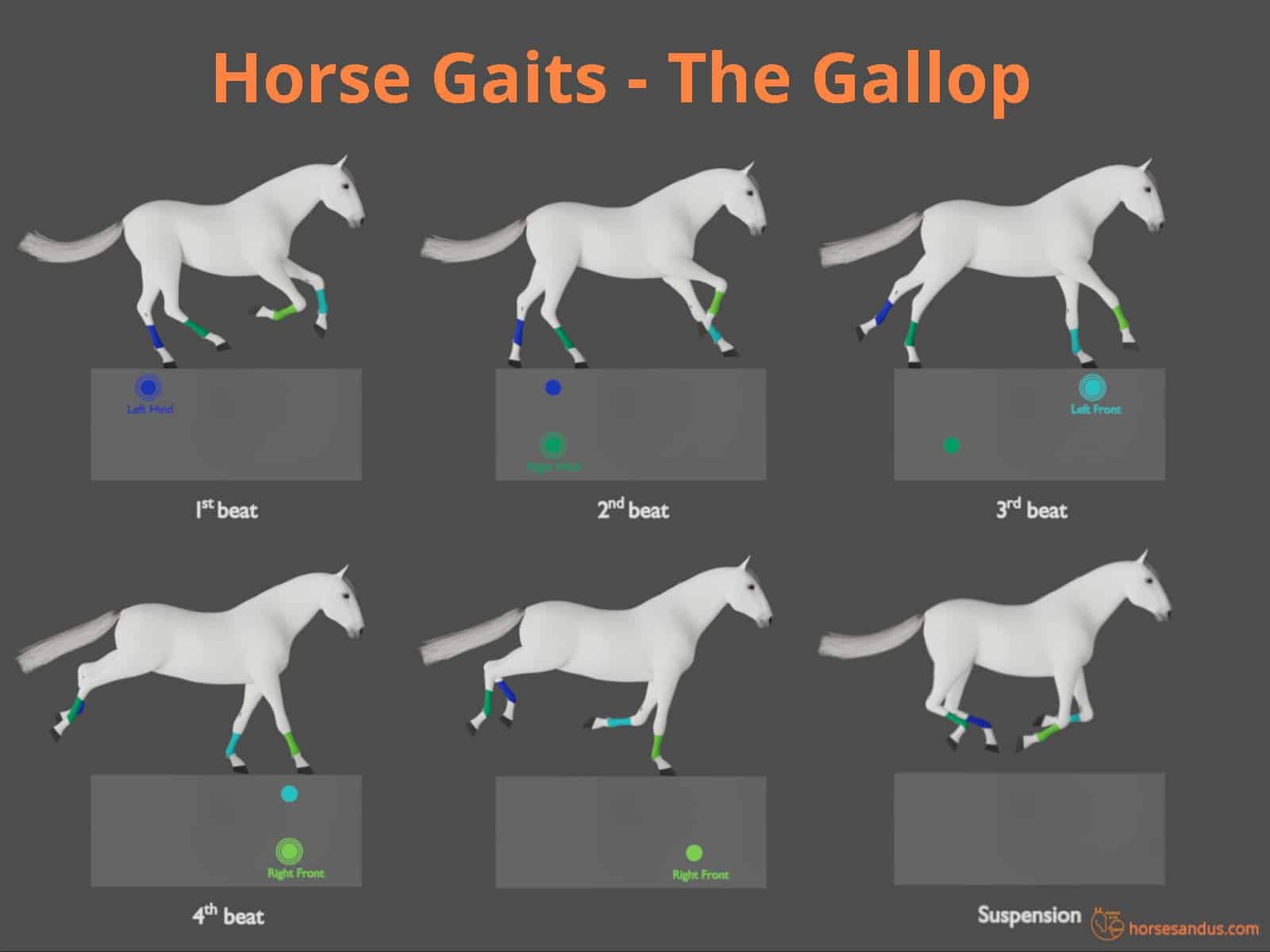

Horse Gallop

The gallop is the horse’s fastest gait. It is an asymmetrical four-beat gait, characterized by four distinct beats, one hoof at a time, followed by a moment of suspension. The footfall sequence is similar to the canter, but the canter´s second beat is extended to two beats due to the longer stride length, making the gallop a four-beat gait.

The footfall sequence is:

Right Lead Gallop

Left Hind – Right Hind – Left Front – Right Front – Suspension

Left Lead Gallop

Right Hind – Left Hind – Right Front – Left Front – Suspension

This sequence is repeated in a regular cadence: 1,2,3,4, pause, 1,2,3,4,pause,…

The Leading Limb in the Gallop

The gallop can be either in the right lead or the left lead, and the horse will often change the lead when the leading leg gets tired. The more fatigued the horse is, the more frequently he will change lead.

In the gallop, the head and neck move forward and backward to maintain the horse’s balance.

The gallop is the horse’s natural speed gait. He will transition to it whenever he wants to maximize its speed. In the wild, it is used to run away from predators, and so horses evolved to be sprinters.

Variations Of The Gallop

The gallop can vary in speed and endurance depending on the need of the horse or the rider.

Cross-country gallop is a moderate speed gallop, around 13 to 25 miles per hour (20 to 40km/h), that can be maintained during long distances. This gallop is also called “hand-gallop” because it is a more controlled gallop but should still have 4 beats. It is ridden in hunting events.

Racing gallop is the fastest gait of the horse, around 25 to 30 miles per hour (40 to 48 km/h), that can only be maintained for short distances. This gallop is ridden in horse races.

Sprint gallop is a very fast galloping speed, approximately 45 miles per hour (72km/h) achieved by the American quarter horse, during a very short distance, usually a quarter-mile, hence the name Quarter Horse. Speeds of 55 miles per hour (88.5 km/h have been registered).

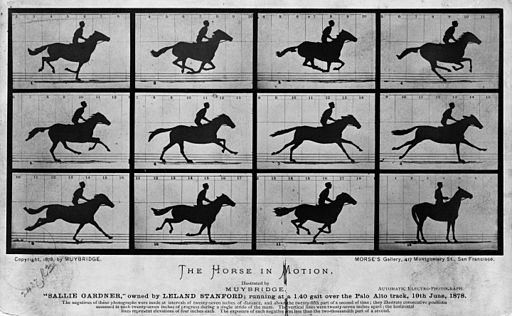

History of The Horse Gallop Controversy

Horses gallop so fast that the human eye can’t see this gait’s details clearly. So until the 1870’s the motion of a horse’s gallop was not really understood.

The classical paintings depicted horses with all four legs stretched out during the suspension phase.

Both scientists and the general public debated for many years whether or not the horse’s feet came off the ground when he was galloping.

In 1872, Leland Stanford, the man who founded Stanford University, and also bred thoroughbred horses, believed that technology would settle the existing controversy about the horse’s gallop.

He commissioned the photographer Eadweard Muybridge to photograph a running horse.

The result was a document known as The Horse in Motion, in which the photographs clearly showed the horse with a moment of suspension with all four hooves off the ground. However, the suspension phase was when the legs were bent, not stretched like it was depicted in the classical paintings.

What Is The Difference Between A Canter And A Gallop?

The canter and gallop are related gaits, and in many parts of the world, there is no word for canter, and both gaits are called gallop. However, there are differences; the gallop is faster, has a longer stride length, and more beats. The canter is a three-beat gait, while the gallop is a four-beat gait.

Differences between canter and gallop

| Canter | Gallop |

|---|---|

| Slower Gait | Faster Gait |

| Shorter Stride | Longer Stride |

| 3-beat gait | 4-beat gait |

| Hindlimbs are used for propulsion | Forelimbs and hindlimbs are used for propulsion |

| Shorter suspension phase | Longer suspension phase |

| Used in all disciplines except racing | Used in cross country and racing |

Gait Transitions In Horses

Transitions are changes from one gait to another, and in nature, horses make transitions easily and automatically. As the horse increases its speed, he will transition to another gait to minimize the energy required to move.

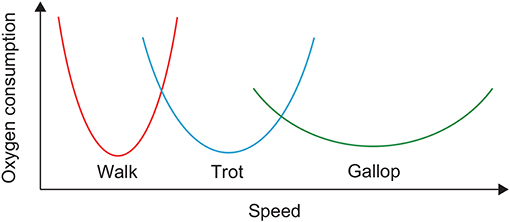

As can be observed in the graph (source), “adjacent” gaits share a common speed range (walk and trot, and trot and gallop), and within that speed range, the horse will transition to the gait that consumes less energy.

In nature, the horse moves through the gaits sequentially. However, the ridden horse can be asked to skip gaits, which is much more difficult for the horse, so both rider and horse must be properly trained to do these transitions correctly.

An interesting article about riding horse transitions can be found here.

Sources

Horse Gaits, Balance, and Movement, Susan E Harris, available on amazon.

The dynamic horse, Hilary M. Clayton, which is available on amazon.